By Stella Loutsou

Introduction

Just over 45 days into Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine, its results on the rest of the world have already emerged. Over the course of the last few weeks, the West’s reaction, and the sanctions it already imposed on Russia have raised the question of it oil and gas dependence on Russian imports. In this context, the western world is on a quest of alternative suppliers, as well as ways to counteract energy price rises. As far as alternative suppliers are concerned, all eyes seem to be on the area with the largest natural gas reserves among members of the OPEC, the Middle East, and more specifically Iran. But where does Israel come into play in this context?

Sanctions imposed on Russia

Several countries have imposed or are considering imposing sanctions on Russia following the invasion, with the US naturally taking the lead in the mobilization to target Russia’s economy. On March 8th, US president Joe Biden announced a total ban on all imports of oil and gas from Russia; these imports according to the US Energy Information Administration amounted to only 3% of the country’s total crude shipments and 8% of its oil imports overall. These percentages show how little the US depends on Russian supplies, in contrast to the much larger European Union’s dependence.

According to the European Commission’s Eurostat database, a striking 46.8% of the EU’s natural gas imports and 24.7% of its petroleum oil imports in the first semester of 2021 came from Russia, an increase from 2020. President Biden, on his statement regarding the total US ban on Russian oil imports, acknowledged these figures and the fact that the EU could not possibly follow through with a similar ban, stating that “The United States produces far more oil domestically than all the European countries combined… we can take this step when others cannot, but we’re working closely with Europe and our partners to develop a long-term strategy to reduce their dependence on Russian energy, as well.”.

The Iran nuclear deal – talks of a revival?

Following the US’ total ban of Russian oil and gas imports and the concerns of the international community in general, proposals have resurfaced regarding the revival, in one form or another, of the Iran nuclear deal of 2015.

The Iran nuclear deal, formally Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) is an agreement on the Iranian nuclear program reached in July 2015. Under the US presidency of Barack Obama, the nuclear deal was agreed between Iran on the one side and the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council plus Germany on the other, along with the participation of the European Union. Its goal was to restrict Iran’s nuclear program and to prevent it from becoming a nuclear weapons state, in fear that such a development would trigger new tensions in the wider region, notably with its rivals Israel and Saudi Arabia. According to the terms of the agreement, Iran agreed to nuclear restrictions such as to cease producing the principal nuclear weapon fuels uranium and plutonium, as well as to use its facilities predominantly for medical and industrial research purposes. Iran also agreed to open these facilities to extensive international inspection from the United Nations’ International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). In exchange, the rest of the signatories agreed to a considerable easing of previously imposed sanctions on Iran worth billions of dollars. This included a US sanction lift on oil exports, as well as lifting a UN ban on purchases by Iran of conventional weapons and ballistic missiles. This UN ban was planned to be lifted five years after signing the deal, on condition that Iran still complied with the terms.

The JCPOA worked in Iran’s favor, the economy of which was in a deep recession before its implementation, with the International Monetary Fund reporting that the country’s real GDP grew by 12.5% the first year following the agreement. The deal, however, took a different turn when US president Donald Trump announced on 9 May 2018, that the US would withdraw from the agreement, over claims that the deal was not enough to prevent Iran from developing nuclear weapons. Following this announcement, the Trump administration went on to reimpose sanctions which were in place prior to the nuclear deal or even additional ones. These sanctions covered a variety of Iran’s sectors, including the oil sector, its Central Bank and most of its state-run and private banks. They also included several individuals and companies. Lastly, the US also imposed sanctions on non-Iranian companies doing business with Iran, which discouraged further international investments. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates supported Trump’s campaign against Iran, while tensions escalated with attacks on oil shipments, a strike on a Saudi oil facility and the US assassination of Iran’s most powerful general, Qasem Soleimani, in 2020.

Under the Biden presidency, on the contrary, suggestions regarding a possible revival of the Iran nuclear deal and what that would entail, had resurfaced even prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, as of around April 2021. Negotiations, however, were put on hold due to the Iranian elections in June, in which hardline cleric Ebrahim Raisi was elected president and took office in August. President Raisi, while he previously opposed the JCPOA, stated around his election period that he would be open to negotiating an international nuclear agreement if it took Iranian interests into account. Consequently, negotiations resumed the subsequent months.

On 4 February 2022, the Biden administration, to facilitate and move forward these negotiations, restored a sanctions waiver to Iran which had been rescinded by the Trump administration in 2020. This waiver allowed Russian, European, and Chinese companies to carry out work at Iranian nuclear sites if it was non-proliferation work. More specifically, this meant that they could carry out work which didn’t entail the production or spread of nuclear weapons. On February 8th, a meeting was held in Vienna between Iran and several world powers, during which the Iranian delegation stated their demand for all sanctions imposed by the Trump administration to be lifted. The US administration replied it is willing and prepared to lift all sanctions “inconsistent” with the deal. However, on March 30th, the US imposed sanctions on several entities involved in a procurement of “ballistic missile propellant-related materials”. According to the US Treasury Department, these materials were procured for an Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRCG) unit responsible for research and development of ballistic missiles.

These sanctions were seen by the US as a way of reinforcing their “commitment to preventing the Iranian regime’s development and use of advanced ballistic missiles”. On the contrary, from the perspective of the Iranian foreign ministry it was seen as “another sign of the US government’s malice towards the Iranian people”. This back-and-forth situation between the two countries continues even more intensely in the context of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, due to the uncertainty of the situation. In fact, Russia recently published a list of security guarantees it demands from the US and NATO. One of these demands is that the US sanctions imposed on Russia after its invasion of Ukraine will not get in the way of Russia’s ability to trade with Iran.

Israel amid Iran nuclear deal revival talks

The effects of these latest developments are not and could not be limited to the directly involved country, Iran, but spread to the entire Middle East. Israel, notably, is one of the main countries actively threatened by a possible revival of the Iranian nuclear deal.

The withdrawal of the US from the JCPOA was believed, at the time, to be a victory for the former Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu. In the long term, however, the sanctions imposed by the US and Israel’s attempts to hinder Iran’s nuclear program were proven to have the opposite effect. As of 2018, Iran had been stepping up its uranium enrichment. Experts presume that, should it wish, it would be able to possess functional nuclear weapons within two years. Furthermore, Israel worries that, were Iran to receive sanctions relief and billions in released frozen assets due to a revived deal, the money would go into empowering Iran’s regional ambitions. There are Iranian-funded groups in Syria and Shia militias in Iraq which Iran has influence on, while Iran also considers Yemen’s Houthi rebels its partners. Israel sees them as a threat to its security, in addition to Lebanon’s Hezbollah and Palestinian militants in the Gaza Strip, which it is already engaged in campaigns against.

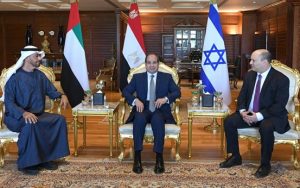

In this context, Israel, attempting to send a message to Washington, chose to follow a quite unorthodox strategy; strengthen its ties with the rest of the Middle Eastern and Arab world based on a common opponent. On March 22nd, Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett met with Egypt’s Abdel Fattah el-Sisi and the UAE Mohammed bin Zayed to discuss the increased oil prices, as well as the Iranian nuclear talks in Vienna, with the additional aim to create a coalition which would include Israel, Egypt, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Jordan and even Turkey, against Iran. Israel is also trying to convince Saudi Arabia (the biggest producer in OPEC) and the UAE to accept US calls to increase their oil production capacity to reduce the world’s dependence on Russian oil and ease energy prices.

Conclusions

The Iran nuclear deal is an agreement which, in around seven years thus far, has managed to go through great turbulence while massively challenging not only Iran’s economy but also the energy and trade sectors internationally. Three different US administrations have had to deal with it so far, from its signature after a period of deep recession in Iran with the Democrats in the White House, to the US withdrawal during the Trump administration, to talks regarding its revival resurfacing once again with the Democrats in power. The attempts to bridge the gaps between the two most directly involved countries, the US and Iran, continue to move back and forth, with one side constantly accusing the other of either hesitation or bad faith. Meanwhile, the ongoing invasion of Ukraine is contributing to the ever-growing uncertainty of the negotiations, while Israel finds itself watching from the sidelines, attempting to gather as much support as needed to send a message to Washington.

For further reading:

- https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/what-iran-nuclear-deal

- https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-03-07/how-an-iran-nuclear-deal-could-affect-oil-trade-and-security

- https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/2/4/biden-administration-restores-sanctions-waiver-to-iran

- https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/feb/25/why-israel-faces-new-dangers-in-shadow-war-against-iran-if-nuclear-deal-is-agreed

- https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/egypt-uae-israel-meet-discuss-energy-price-wheat-iran

- https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/3/28/blinken-and-arab-foreign-ministers-meet-at-negev-summit

Αριστοτέλειο Πανεπιστήμιο Θεσσαλονίκης

Αριστοτέλειο Πανεπιστήμιο Θεσσαλονίκης